Movies and movie cameras

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: September 3, 2018.

Ordinary cameras

are brilliant for taking snapshots of the world. The only trouble is,

the world simply won't "sit still"—there's always something moving around us, over our heads, or even under our

feet. Fortunately, movie cameras can capture moving images that better reflect the changing nature of our world.

Master the art of the moving image and you could be the next king of YouTube—and well on your way to a career in Hollywood! So what are movies and how exactly do they work? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: Thomas Edison's original movie camera.

Credit: Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive,

Library of Congress, Prints and

Photographs Division.

Contents

- "Persistence of vision": How the eye fools the brain

- How movies work

- How movie cameras work

- Film movie cameras

- How a classic movie camera works

- Video cameras and camcorders

- How to make a movie with your phone or digital camera

- Find out more

"Persistence of vision": How the eye fools the brain

Animation: Persistence of vision: I made this little flick book animation by drawing eight frames

(eight separate images) and running them together to make a single animated artwork (an animated GIF). Each frame stays on the screen for 50ms

(50 milliseconds—one twentieth of a second) except the final frame, which lasts 500ms (a half second). Persistence

of vision makes it look like a relatively smooth bit of ball kicking—and it would look even better if I used

more frames and a shorter duration for each.

Open up a movie camera or camcorder (a compact electronic video camera) and you'll find all kinds of mechanical and

electrical parts packed inside. But the basic science behind making

movies has nothing to do with lenses, gears,

electric motors, or

electronics—it's all about how our eyes and brains work.

You've probably done that trick where you make a flick book (sometimes called a flip book) by drawing little stick people on

the corner of a pad of paper and flicking them with your fingers so

fast that they hop, skip, and jump. When your eye sees a series of

still images (or "frames") in quick succession, it holds each image for

a little while after it disappears and even as the next one starts to

replace it. In other words, each picture leaks into the next one, so

they blur together to make a single moving image. This is known as the

persistence of vision and it's the secret behind

every movie you've ever seen.

It's not just flick books that use persistence of vision. Before

movie cameras and projectors were invented, 19th-century toy makers

were using the same idea to make relatively crude animated films. A

typical toy from this era was called the zoetrope. It was a large

rotating drum with thin vertical slits cut into its outer edge. Inside,

you placed a long strip of paper with small colored pictures drawn on

to it. Then you rotated the drum to make the pictures blur together

(just like a flick book) and looked down through one of the slits to

watch them. Here's a great photo of a restored zoetrope by Andrew Dunn.

How movies work

Photo: Few things illustrate how movies work better than Muybridge's

amazing photos. Here's a sequence he made called "The Horse in Motion."

Photo courtesy of US Library of Congress.

It's a relatively small step from flip books and zoetropes to fully

fledged movies. The theory of making a movie is just as simple: you

take thousands and thousands of still photographs one after another.

When you play them back at high speed, they blur into a single moving

image—a movie.

A famous American photographer called Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904)

was one of the first people

to show how one moving picture could be made from many still ones.

Using multiple cameras arranged in rows,

he took series of photographs of galloping horses and vaulting

gymnasts.

How movie cameras work

A movie camera or camcorder simply automates what Muybridge did by hand. Classic movie cameras are largely

mechanical and capture images on moving plastic film; they're examples of what we call analog technology

(because they store pictures as pictures). Modern video cameras and camcorders work more like digital cameras and webcams and capture images digitally instead (storing pictures as numbers).

Photo: At first glance, this old-style Arriflex

film camera looks quite like a modern camcorder—but look closer. On top, you can see a big oval-shaped

case where a huge reel of film is stored. If you were standing next to this

camera, you would also be able to hear a motor inside whirring away as the film

rattled through the mechanism. Photo by Dave Maclean, courtesy of Defense Imagery.

Film movie cameras

A basic movie camera is like a standard film camera that takes

a photograph on to plastic film

every time the shutter opens and closes. In a standard film camera, you have to wind the film on so it

advances to the next position to capture another photograph. But in a

movie camera, the film is constantly moving and the shutter is

constantly opening and closing to take a continuous series of

photographs—about 24 times each second.

Before modern camcorders were invented, people used mechanical home movie cameras, which were very

small versions of professional movie cameras with all the parts (and

the film itself) miniaturized. In these early cameras, the film was moved past the lens

by either a wind-up (clockwork) mechanism

or a small electric motor.

How a film movie camera works

- The unexposed movie film starts out on the large reel at the front. The film and its path through the camera are shown by the black dotted line and the black arrows.

- The film passes over guide rollers and spring-loaded pressure rollers that hold it firmly against the central sprocket (a large wheel with teeth protruding from its edge, rather like a gear wheel). The sprocket's teeth lock into the holes on the edge of the film and pull it precisely and securely through the mechanism.

- Light from the scene being filmed enters through the lens and passes into a prism (shown by the yellow triangle), which splits it in half.

- Some of the light continues on through the shutter (black line) and hits the film, exposing a single frame (one individual still photo) of the movie.

- The rest of the light takes the lower path, bouncing down into a mirror.

- The shutter is like a mechanical eyelid that blinks open 24 times a second, allowing light through when each frame of the film is securely in place and blocking the light when the film is advancing from one frame to the next. The shutter is driven by the same mechanism that turns the sprocket.

- More pressure rollers hold the exposed film against the lower part of the central sprocket. The teeth on the sprocket pull the exposed film back through the camera.

- Light redirected by the mirror exits through a lens and viewfinder so the camera operator can see what he or she is filming.

- Guide rollers take the exposed film back up toward the upper reel.

- The large upper reel at the back collects the exposed film.

Mechanical movie cameras barely changed at all, from their invention in the late 19th century until the development of video cameras and camcorders almost a century later. That's evident by comparing the diagram above with this illustration of one of the very first movie cameras, Thomas Edison's Kinetograph, which dates from 1891.

Artwork: This version of Edison's Kinetograph (which is not the original) took photos onto a film punched with little sprocket holes, just like the classic camera illustrated above. The film unrolled from one large reel (light blue) to another, advanced by a gear wheel with teeth (red) powered by pulleys (purple) driven by an electric motor (orange). The large lens is on the right (green) and the viewfinder on the left (dark blue). From US Patent 589,168: Kinetographic camera by Thomas Edison, patent filed August 24, 1891 and granted on August 31, 1897, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

Photo: A typical piece of film. Notice the little square sprocket holes running down the two edges? The sprocket wheel in the camera locks into these holes to pull the film through the mechanism. If you look closely, you can just about see that there are four frames (four separate still photos) on this strip. The camera shutter opens at precisely the moment when each frame of the film arrives exactly in front of the lens and closes when the film starts to move on to the next frame. And this happens 24 times each second! Without the sprocket holes, it would be difficult to move the film without it slipping and hard to ensure that the frames of the film were correctly positioned to coincide with the opening and closing of the shutter.

Video cameras and camcorders

Photo: A Canon XL1S digital video camcorder in

action. Note the boom microphone on top for recording high-quality

sound. You focus the image by turning the lenses at the front with your

fingers. Photo by John A. Lee courtesy of Defense Imagery.

When video recording was invented, photographic film was replaced by

magnetic videotape, which was simpler, cheaper, and needed no photographic developing before you could view the things you'd recorded.

Modern electronic camcorders use digital video. Instead of recording

photographic images, they use a light sensitive microchip called a charge-coupled device (CCD) to convert what the

lens sees into digital (numerical) format. In other words, each frame

is not stored as a photograph, but as a long string of numbers.

So a movie recorded with a digital camcorder is a series of frames, each

stored in the form of numbers. In some camcorders, the digital

information is recorded onto videotape; in others, you record onto a DVD; and in still others, you record

onto a hard drive or flash memory. The advantage of storing

movies in

digital format is that you can edit them on your computer, upload them

onto web sites, and view them on all kinds of different devices (from cellphones and MP3 players to computers and televisions). Try doing that with a silent

movie from the 1920s!

How to make a movie with your phone or digital camera

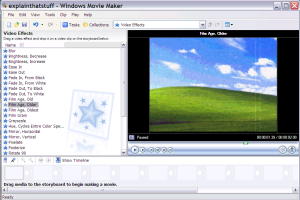

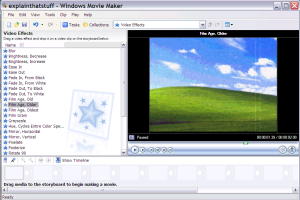

Photo: It's easy to add special effects to your movie with software like Movie Maker, a program packaged with older versions of Microsoft Windows. With a preview of your movie in the right-hand pane, you can click through a whole list of visual effects on the left, including transitions, fade-outs, and making your movie look old and crackly like a silent movie from the 1920s!

Virtually all smartphones (and most digital cameras) let you capture video as well as still

photos, so you don't need a movie camera or camcorder to win an Oscar!

Maybe your ambitions aren't quite so grand: perhaps you'd just like to

record a YouTube video or a holiday film for your family?

If you've never tried home movie making, why not give it a go?

Here are a few basic tips:

- Preparing: Make sure your phone or camera batteries are fully charged before you start. Unlike still photography, which uses battery power only intermittently, making movies means your camera is operating continually for perhaps a half-hour or more—easily enough to drain your batteries

at the most inconvenient moment. It helps to have fully charged spare batteries standing by.

- Planning: Unless you're making a spontaneous home movie, decide what you want to film before you start

recording. You could even draw up a storyboard to help you plan what to film and when. That way,

you can record all the outside shots together, all the inside shots together, and so on—to save

lots of moving around.

- Casting: Who's going to act in your movie? Friends and family? Or maybe you'll just talk to the camera yourself in a kind of video diary?

- Filming: Just like a professional movie director, be sure to record much more footage than you actually need.

That way, you can edit down to a much higher quality end product. If you're working with other actors, record

multiple takes of key scenes and choose the best ones when you watch them later.

- Editing: Explore your phone or computer and see whether you have any video editing apps or software installed:

- On Android, check out apps like

VideoShow and

Magisto.

- On iPhones or a desktop Apple Mac, try iMovie.

- If you're a Microsoft Windows user, see if you have an old program called Movie Maker installed. It lets you load files you've recorded with a digital camera or webcam and then edit them frame by frame, adding text titles and all kinds of other visual effects. Since 2017, Microsoft no longer supports Movie Maker

for use with Windows 10, but it might still be installed on your machine if you have an older version of Windows, and there are various third-party alternatives for Windows 10 users.

- Publishing: Once you've recorded and edited your movie, decide what you'll do with it next. How about burning it onto

DVD and giving it out to your friends and family? Or maybe you could upload it to YouTube or Facebook and

become the next overnight movie sensation?

Find out more

Books

Practical guides for younger readers

Practical guides for older readers

History

Please do NOT copy our articles onto blogs and other websites

Text copyright © Chris Woodford 2008, 2017. All rights reserved. Full copyright notice and terms of use.

This article is part of my archive of old material. Return to the list of archived articles.