Sunscreen

by

Even when we're outdoors, we're

inside—inside

an amazing, flexible, self-repairing container called skin! Few things

are quite so amazing. Skin stretches as you move and grows as you get

older. Like a hi-tech

Photo: Sunburn or tan? By the time you can tell the difference, it may be too late already. Don't be a fool: stay safe. Put on plenty of sunscreen, apply it evenly, and don't rub it in too much if you want it to be properly effective.

Why do we need sunscreen?

Have you noticed how you can get sunburned on a cloudy day, and even

when you're

There are actually three different kinds of ultraviolet in sunlight: UVA, UVB, and UVC. UVC is the most harmful, because the energy waves it contains have the highest frequency and the most energy. Fortunately, it's entirely filtered out by Earth's ozone layer and none of it reaches Earth, so we don't have to worry about it.

What we do have to worry about are the other two types of ultraviolet light. UVB is less harmful than UVC, because its energy waves are less energetic, but it's still more energetic and harmful than UVA. Both UVA and UVB can pass through the ozone layer, though much of the UVB is filtered out and most of the ultraviolet light that finally reaches Earth's surface is UVA.

Photo: Suncreams like this promise protection against both UVA and UVB. The large number on the bottle is the sun

protection factor (SPF). Suncreams with the highest numbers offer most protection. They allow you to stay out in the Sun for longer with less risk of damaging your skin.

Why is this a problem? UVB causes sunburn (a painful first degree burn with some reddening and swelling of the skin) and other surface skin problems such as skin cancer and premature aging. Scientists think UVA (which penetrates deeper) is important in causing damage to the deeper layers of our skin.

Generally speaking, all you need to remember is that ultraviolet light (both UVA and UVB) can be harmful to your skin. Because you can't see the damage you're doing until it's too late, it's a good idea to protect yourself by staying out of the midday sun (the safe times depend on the time of year and where in the world you are), and wearing loose-fitting clothes, sun hats, and sunscreen.

Natural sunscreens

Nature's a pretty clever thing. It solved the sunburn problem for us a long time ago with two very handy mechanisms.

First, we have the ozone layer—Earth's natural sunscreen. Ozone is a

special kind of oxygen gas that gathers in the stratosphere, the

highest layer of Earth's atmosphere that is about 19–48 km (12–30

miles) above sea level (that's way beyond the height at which

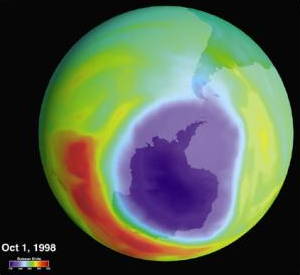

Photo: The ozone layer helps to protect us from harmful solar radiation; ironically, we've not returned the favor: our use of ozone-depleting chemicals caused this huge hole to appear over Antarctica. Picture courtesy of NASA on the Commons.

Holes in the ozone layer are very serious, because they mean more harmful ultraviolet light can get through and damage people's skin. A few years ago, the US Environmental Protection Agency (the government body responsible for helping to avoid threats to the US environment) estimated that a 40 percent loss of ozone by the year 2075 could lead to 154 million extra cases of skin cancer and 3.4 million more deaths.

The other natural sunscreen we have is built into our own skin. If you're a white-skinned (Caucasian) person, you'll have noticed that your skin darkens very gradually in sunlight: you get a sun tan. What happens is that sunlight stimulates skin cells under the surface called melanocytes. These produce a pigment called melanin, a natural coloring that moves toward the surface of your skin, giving it that attractively brown, tanned appearance. After a while, the melanin in your skin provides a certain amount of protection against ultraviolet light. People with naturally darker skin have more melanin in their upper skin layers and naturally greater protection from ultraviolet light.