Telephones for the deaf and hearing impaired

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: September 23, 2020.

Do you ever find it tricky communicating by

Photo: This telephone for hearing-impaired people, designed by Geemarc,

has lots of extra features. You can amplify the headset and

microphone volume. There's a loud ringer and a

Contents

Amplifying phones

Photo: Deaf and hearing-impaired people rely on visual information to a much greater degree, like these two people communicating through sign language. But most can still use telephones and related technology as well. Photo by Wendy Beauchaine courtesy of US Air Force.

The simplest and crudest solution to improving a phone for someone

with a hearing impairment is obviously to make it louder.

On an

Amplifiers for existing phones

If you like your existing phone and your hearing difficulty is more moderate, you could invest in a

telephone amplifier. The simplest ones are little boxes that clip or strap onto the handset earpiece

of a normal phone. They have a microphone one side (which faces the phone loudspeaker), a loudspeaker the other

(which faces your ear), and a

Artwork: How a simple telephone amplifier works. This one is a headset that can pick up sounds either from a built in microphone or an inductive coupler (explained in more detail below). You hold the phone handset (green) near the microphone (blue) and an amplifier in the ear units (red) boosts the sound into two small speakers (yellow) that pass sounds either directly into your ear canals or to your conventional hearing aid. Artwork from US Patent 5,086,464: Telephone headset for the hearing impaired by Alvin F. Groppe, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

More sophisticated "in-line" amplifiers fit in between the handset and the base unit so they interrupt and boost the current going from the base to the handset loudspeaker, making the sound louder that way. Some have tone controls for added refinement of the amplified sound. Generally, amplifiers like this boost volume by about 20–40dB.

Photo: An in-line telephone amplifier is a little box that fits between the handset and the base of a conventional phone. To use one of these, you'll need a reasonably modern phone with a detachable handset that links to the base with a standard RJ11 connector. In-line amplifiers take about a minute to connect.

Identifying calls and callers

Phones for the hearing impaired generally have much louder rings

(a maximum ring volume of 80dB is typical) and visual or vibrating

alerts (bright flashing strobe lights or vibrating buzzers similar to

those in cellphones and

Photo: A typical plug-in ringer. This one, made by BT in the 1980s, has an electronic beeper and a flashing red LED lamp. It fits into a standard telephone socket with an RJ11 connector.

Inductive coupling

Photo: In movie theaters and concert halls, look out for signs like this that indicate induction loop hearing assistance is available. The same technology is built into hearing-aid-compatible telephones, which generally have a T switch on them somewhere.

A

When those sounds are produced by a loudspeaker of some kind, such as the one in a telephone, a person with a hearing impairment can often produce a clearer, more audible sound in their ear by induction coupling: linking their hearing aid directly, electromagnetically, to the sound source and switching off the microphone in their hearing aid. Public places such as theaters and concert halls are often fitted with induction loops, which are large circuits of wire fed with electrical signals from the same source driving the main loudspeakers. As the signals travel around an induction loop, it produces a small, safe, fluctuating magnetic field all around it. Compatible hearing aids will pick up these fields using a smaller loop of wire (called a "telecoil") inside them and convert them directly into sounds. Effectively, you get a direct "feed" of the loudspeaker to your ear, so your hearing aid receives only the sounds you want to hear and not the background noise. Compatible hearing aids have a switch on them called the T setting that allows them to pick up signals from induction loops. Virtually all phones designed for hearing impaired people can be used with inductive coupling in this way.

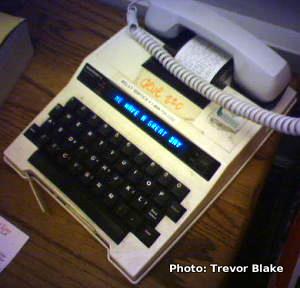

TTY telephones

Photo: A typical TTY phone, probably dating from the 1980s. Note how the phone handset sits in an acoustic coupler on top. There's a keyboard for sending messages and a one-line display for receiving them. There's also a little printer (under the phone handset in the center) for printing out conversations. Photo by Trevor Blake published on Flickr under a Creative Commons Licence.

If you have a profound hearing impairment, technologies like amplification and inductive coupling may be little or no use. One solution is to use a telecommunications relay service (TRS) and a TTY (teletypewriter) phone (also known as a minicom or textphone in some countries), which looks a bit like a laptop computer with a keyboard, a small (typically one-line) display, and two round plugs at the top where you sit your phone (sometimes called an acoustic coupler).

TTY phones can be used in various different ways. If both users have TTY equipment, you can

simply type messages at one end and have them appear on the display

at the other end. If a user with a conventional phone wants to

communicate with someone who has only a TTY phone, typically they'd

speak to an operator who'd listen to the words, type them out, and

relay them over to the display on the user's TTY phone. Although many people still rely on

TTY phones, they're less relevant now alternative technologies exist,

such as

Cellphones

Photo: Cellphones have traditionally been difficult for hearing-impaired people to hear clearly, but they're now improving rapidly thanks to advances in technology and changes in legislation.

Some countries have been more responsive to the needs of

hearing-impaired people than others. In the United States, it's over

20 years since Congress passed the Hearing Aid Compatibility Act of

1988, effectively prompting phone manufacturers to make more of their

equipment usable by hearing-impaired people.

With or without legal prompting, phone makers now realize it's in their own commercial interests to make more effort with accessibility. Some of Google's Android phones, for example, come with a built-in Sound Amplifier that allows you to fine tune headphones to help compensate for particular forms of hearing loss. Apple, meanwhile, has taken steps to make iPhones, iPads, and iPods compatible with dozens of hearing aids produced by leading manufacturers including Amplifon, Beltone, Philips, ReSound, Rexton, and Signia.

Cellphone alerts

Telephones are only useful if you can detect that they're ringing. While desktop phones for hearing-impaired people have things like strobe lights to indicate incoming calls, cellphones, being much smaller and typically riding in your pocket, don't always have the same features. There are solutions, however. Most cellphones have a discreet vibrating alert, so that's the simplest way to use them if you can't hear them ringing. You can also get desktop holders for cellphones that detect the vibrating alert for a call or text message and flash for a minute or two. They're produced by manufacturers such as Serene Innovations (which makes one called CentralAlert™) and Dreamzon (which sells a popular model called LightOn; here's a video demonstration of LightOn).

Apps

Search for "hearing impairment" (or similar) on your favorite app store and see what comes back. You might be surprised at some of the ingenious things you find. How about Soundprint, for example, which helps you locate quieter places to socialize with your friends. Or numerous apps that you let you control your hearing aid from your phone using Bluetooth®. Also well worth a look is Google's Live Transcribe (for Android and iOS), which very quickly and accurately converts spoken words into text you can read from your phone screen.

Find out more

On other sites

- Hearing Aid Compatibility for Wireless Telephones: This article from the Federal Communications Commission sets out what help you can expect from wireless service providers.

- Telecommunications Relay Services (TRS): Another useful article from the Federal Communications Commission explains everything you need to know about TRS in the United States.

- Independent living if you are deaf or hearing impaired: A helpful summary of advice from the UK government (via the Wayback Machine).

Helpful organizations

- USA: National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders: Lots of general background about hearing loss and deafness.

- USA: Hearing Loss Association of America: The (US) nation's voice for people with hearing loss. Their telephony page covers landline and cellphones, captioned phones, and state equipment distribution programs.

- USA: California: Deaf and Disabled Telecommunications Program (DDTP): What kind of assistance is available and how can you apply for it?

- UK: Action on Hearing Loss: This UK charity, helping the deaf and hard-of-hearing, has a clear, easy-to-use website with lots of good background information. Their store sells various kinds of telephone aids for the hearing impaired, and raises money for the charity.